By Dr Kay Guccione, Head of Research Culture and Researcher Development and Co-Director of the Lab for Academic Culture.

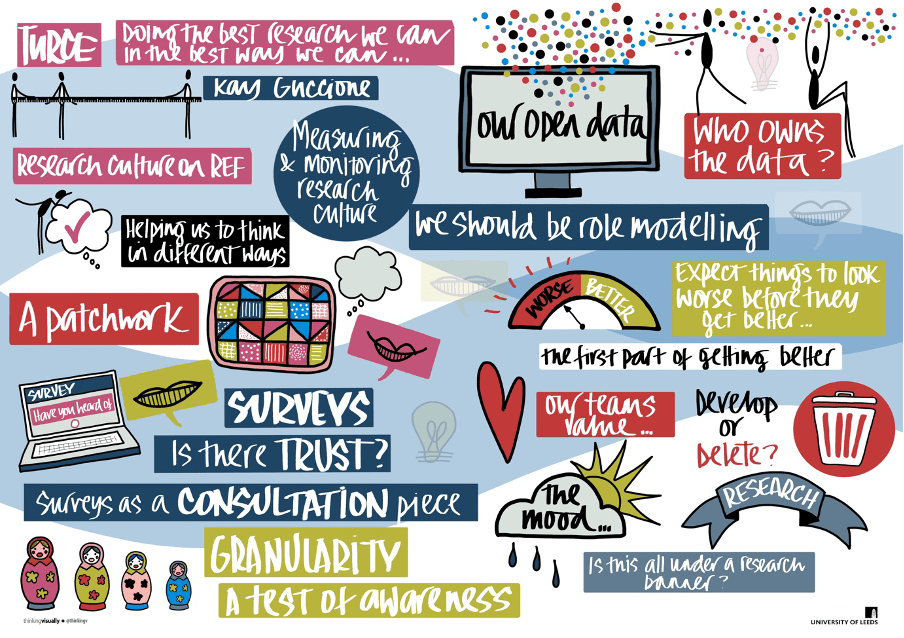

I had a very reaffirming two days thinking time last week at the University of Leeds ‘Unnamed Research Culture event’. The purpose of the event was to discuss how we move forward as a sector in doing, monitoring and measuring the impact of our Research Culture work. The reason the event was ‘unnamed’ was to give delegates the opportunity to discuss the issues we each experience related to doing research culture work, and to surface the ‘what next’ for us as a sector. As I was invited as an individual, not to represent the university of Glasgow per se, my thoughts here in this article also represent my own ideas.

Whilst many of us in various guises have been doing the delivery of research culture projects and initiatives for many years, we are now on the cusp of there being a great deal of funding being determined by documenting the impact of research culture work, and so it’s timely to consider the bigger implications of how we do that – a great shout by our Leeds colleagues.

Dr Rachel Herries (Glasgow’s Research Culture Manager) joined me at the event, the audience for which diverged from the usual Researcher Developer colleagues we tend to mingle with. This brought a welcome medley of perspectives from technical leads, library professionals, EDI specialists, network builders, and the recently appointed (with credit to Research England and the Wellcome Trust) wave of Research Culture Managers, research culture project PIs, and (thanks to REF) People Culture and Environment leads, REF Managers, and one or two Directors of Research and Innovation.

The initial question we collectively responded to in all its expansive breadth was ‘do we need something like a DORA statement for Research Culture?’

DORA is the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment. It’s a statement that reminds us that if we are going to measure and assess the ‘quality’ of research ‘outputs’ we should be very mindful of: how we conceptualise ‘quality’ and ‘output’, what data we have and don’t have that might inform us about quality, not using poor proxies for quality (such as journal impact factor) and the fact that traditional measures of academic success (more papers in ‘better’ journals) tells us more about the career opportunities people have had, than their ability. This significantly disadvantages some groups of people in advancing their career and limits any recruiters using this flawed data to a subset of all the available research talent. In short (and do forgive my rudimentary summary) it asks those doing research assessment work to act with criticality, integrity and openness, based on the limitations of available evidence about research ‘quality’.

Why might we need something like this for Research Culture work?

We are looking at a positive change to how university research will be judged and rewarded. With the 2029 REF team currently considering how to increase the importance placed on ‘People Culture and Environment’ we anticipate a closer scrutiny of how research is done and how researchers are treated. We also fear we could be opening the gates to the potential for universities to compete to be ‘the best’ at research culture, with competition driving siloing, resource grabbing, and reducing our collaborative capacity for systemic change in the sector. Or that prizes will be given more for the quality of the REF PCE narrative that is submitted, than the genuine quality of the research culture.

Some of us feel it’s timely therefore that we who work in this space make sure we also are measuring the right things with integrity, not using poor proxies such as ‘attendance’ as a measure for ‘learning’, or ‘training’ as a measure for ‘capability’, or ‘policy’ as a proxy for ‘practice’. We also want to make sure that we have a shared understanding of the range of people and phenomena that should be evidenced within the PCE bracket, not disadvantaging any groups (or leaving them out of the equation altogether for example our Research Professional colleagues). We are also concerned with what expectations this activity will set between universities and their employees, who may imagine we hold more (complete) data than we really do, or who may not have the full picture of how long it can take to shift a research culture. These issues and more were all part of the discussion.

A 10-minute provocation

The day opened with 10-minute ‘provocations’ offered by community members based on their own experiences. In mine, I talked about the different data types we hold in the course of our culture work, what data we have ready and abundant access to, and what we struggle to collect or access. I called attention to the data we might have overlooked, and the data that we might need to think carefully about whether we want to come to us. I talked about the potential for issues to arise as we seek to use data about our culture to demonstrate progress and impact, at scale, in large organisations. I covered the following 5 points:

- The limitations of Research Culture Surveys. Useful perhaps as a tool for wide consultation in the initial phases of an institutional action plan, the institutional surveys I have seen are not granular or robust enough to detect conclusive longitudinal impact and are as likely to pick up the national mood as the local environment. That is if anyone is still completing surveys these days anyway. Culture Managers wishing to use surveys should beware! A poor instrument showing no discernible improvement will leave people questioning the value of your team.

- The need for us to model open data and get ethical approval. I asked colleagues to consider how they are able (or enabled), as research professionals, to access and engage with ethical approval and open research practices in order to get findings out to the sector as quickly as possible. Some places are still not set up to train and support professional staff with what every academic colleague has unquestioned access to.

- Data ownership and partnership working in institutions. As one colleague on the day remarked, “the system we have created has been perfectly designed to give us what we have got”. Our internal systems for collecting and sharing research culture data in many cases were not consciously designed but patched together over the last decade. Many colleagues experience blocks to internal data sharing via gatekeeping, technology fails, or plain and simple lack of staff resource for data preparation and analysis. I suggested that we need to get to know our colleagues who are data owners ASAP, include, collaborate, build trust, befriend (nay, charm) them, and forge partnership working that enables more easy and automated data flow.

- That we should expect new data sources to highlight more problems. When we start to collect data on a particular phenomenon, we reveal it, bringing it into the light. This is actually a positive and necessary first step in solving problems, but in a competitive process where millions of pounds are at stake, my not be seen that way. We as culture practitioners have to work with the tension of characterising the issue, and at the same time needing to maintain face. We need to create ways be honest and open with each other about this.

- How do we deal with upsetting data? Research culture work generates many positive stories, but also many deeply troubling accounts of experienced frustration and even trauma – solicited and unsolicited. In our teams, how are we collecting, storing, and analysing sensitive and emotionally demanding data. How are we supporting our staff to process and debrief what we have heard or read? Are we prepared to do the work now to create clear cross-institution support processes for colleagues who need a more specialist duty of care?

The energetic discussion that followed showed these points had resonated and were commonly experienced as problematic for many of the attendees within the context of their organisations. A ‘DORA for Research Culture’ could in fact help to establish some needed ground rules for this work across the sector. But also, as one delegate pointed out, we shouldn’t call it DORC!

Next steps

This event was openly presented as ‘the start of something’, and our endeavours are now a work in progress towards whatever that ‘something’ could be. Whilst ‘do we need a DORA for Research Culture?’ was the springboard for our conversations it should be noted that the diversity of role, position, experience and authority in the room, meant that we also considered how best to access network building with our colleagues, as well as practice and data sharing for research culture work. Great questions were raised about how a ‘statement’ differs from a ‘concordat’, whether we really need ‘something else to do’, and how the mission behind such a movement would be best articulated in order that it can gain traction. The data generated by the group was left in Dr Emma Spary, Sam Aspinall and Katie Jones’s capable hands at Leeds, with the idea to reconvene once all the ideas and discussions have been analysed and themed.

What was clear, through the concluding activity of the two-day event, is that a lot of voices were missing from the room, from individuals we could each name, to entire organisations, and from key owners and gatekeepers of institutional processes and systems (and the data they generate), to representatives from the varied staff and student groups that make up our research ecosystem. This widening of the conversation will be part of the next steps. I have indicated strong enthusiasm for helping the to drive the collective ‘what happens next’ , and await the call to action. Meanwhile, what are your thoughts?

I worry that we might observe the same thing happening with culture that we can see in impact. The introduction of impact as part of the formal assessment did drive some really positive changes in understanding, behaviour, process and practice — but the awareness of a constant round of looming future assessments and the linked rewards for good results has also driven an often mechanistic and narrow mindset to ‘doing impact’ that can discourage the reflective approach to research that enables understanding, and planning, for potential impact generation. It can be difficult to retain the good practice needed when the audit culture push is so insistent.

LikeLike

One to watch for sure. On the flip side, if we see the increase in awareness of the work, and uplift in people resource that putting Impact in REF has created, I’ll be happy.

LikeLike