By Kay Guccione, Head of Research Culture and Researcher Development

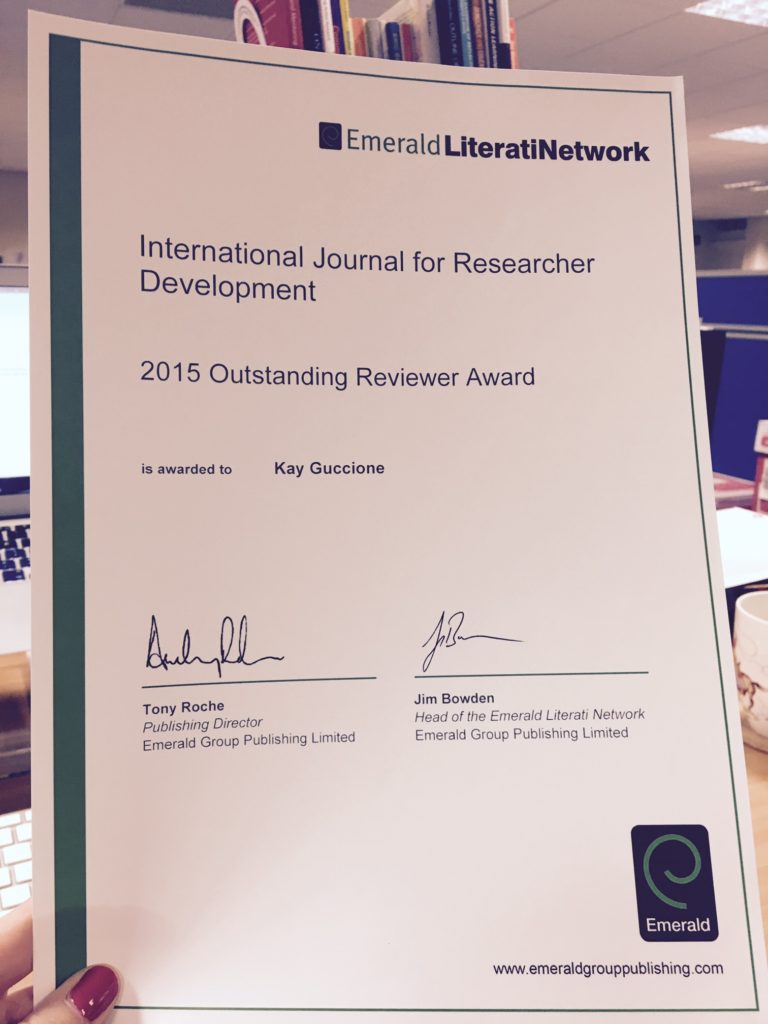

I’ve been selected as ‘Reviewer of the Year’ by a couple of journals and it’s fair to say that this particular recognition is one that really resonated with me and has stayed with me over the years. As a professional coach and mentor, and as a manager and team leader, being good at feedback, and helping others to be, is something I’m a strong advocate for.

Giving feedback that helps people develop is a core competency of being a good researcher, teacher, supervisor, manager and mentor. There are obvious clear benefits of giving feedback in support of learning, but did you realise there are risks too? A small research study I led for Advance HE in 2017, looked at how trust is built and broken between PGRs and their supervisors, and guess what – the giving and receiving of feedback was a key site of trust breaking and added emotional labour.

This is because putting ourselves in a position to receive feedback is one of vulnerability. Whilst with the right frame of mind we as recipients can absorb feedback as just another part of our professional development, avoiding defensiveness takes a certain level of emotional maturity and resilience, and a base level of confidence brought about by experience. So, what can we do, as feedback givers, to adjust our approach for those who may be less confident in themselves, newer to the game than we are, or less emotionally resilient right now? How can we make feedback a site of trust building?

How to give feedback that the recipients will hear, analyse, and respond to.

Giving feedback that acknowledges areas for improvement, and that doesn’t cause the receiver to feel ashamed, close down, clam up, be upset, get defensive or argue back, is really difficult. This is because effective feedback is dependent on more than the structure or mechanism you apply — the relationship between giver and receiver really matters. Additionally, their relationship to their work, career, or the behaviour or decision you are critiquing, will impact on how the feedback is heard and processed. In cases where the feedback is out of alignment with how the recipient sees themself, they can feel really aggrieved. Haven’t we all received feedback that jars with our self-image and thought, ‘You clearly don’t even know me!’.

There is still widespread usage of a formulaic ‘sandwich’ approach to giving feedback (Whitman & Schwenk, 1974) that goes: ‘good bit, critical bit, good bit’. At the time of publishing 50 years ago, it paid service to medical education, but has become outdated for use today, because the recipient (a) always knows what you’re doing, and so (b) dismisses the positive bits and still feels defensive about the critical bits. This is because using a formula can seem to the received to be generic, or disingenuous, and we all know of the temptation to write the criticism first and then add in some positive ‘filler’ to cushion the blow.

So, if it’s not the balance of positive and negative that makes feedback effective – what is it?

Below are some concepts related to the giving of feedback for you to think about. This isn’t a ‘how to’ model because there’s not one right way that works for every person, every time. All that’s required of you, is for you to think about these ideas, think about your feedback, and notice where these suggestions could or wouldn’t work for you.

Consider as you read each idea below, that as supervisors/PIs/managers we intend to stay with the idea of ‘person-centred’ feedback. The key to giving feedback that supports thinking, learning, and motivates action, is to make the feedback about the recipient. Not generic, not illustrated through comparison to someone else, and not about ourselves:

Understand that relationship, rapport and alliance matters. Most of us are more inclined to hear a difficult truth from a trusted colleague, one whom we feel has got to know us and who has got our back, than we are to hear it from someone we already feel tense around, or whose opinion we don’t particularly value. Build your alliance.

Play the ‘long game’ of feedback. Does it matter more to ‘be right, right now’ or is it more important to build a productive partnership that will weather difficulties, and where honest conversations can happen? Ask yourself: do you really need to pick them up on that typo? Must you leap in and correct them? Are you helping them to learn or are you ‘showing what you know’? Are they doing things wrong, or are they doing it in a different way to how you would?

Ask don’t tell. Before giving your opinion, why not ask your mentee or colleague how things went/how things are going, and what they think? For example, “Well done on getting [X] done/drafted, how did it go? Are you pleased with it? Did you find it straightforward? Was there anything more complicated you had to deal with? Is there anything further you’d like to improve about it? Do you have any questions about it?” Questions are great for prompting self-evaluation and often people will do the bulk of the work themselves.

Let go of values-based judgements. If a colleague or mentee’s work contains typos or mistakes, or is otherwise not up to your own standard, it’s not very likely that mistakes were made in order to directly offend you, or as a mark of disrespect. If you’re feeling angry with them, what are you really angry about? What does the anger relate to? Who are you angry with? How are your anger levels generally? It may be that this perceived slight, or lack of care, is a further irritant in a relationship that’s already not working well. Address the cause, not the symptom.

Reject passive–aggressive responses, for example ‘hinting’. Good feedback is built on open and honest conversations. Say what you mean and mean what you say – take a look at this article on how to spot passive aggressive behaviour. If you need to practice getting out of passive aggressive habits, and communicate more honestly, imagine your response will be publicly available – does that change how you will reply?

Be culturally aware. Here’s an article helping you think through your communication habits if you are working with people from different organisational and educational cultures, and diverse nationalities. The ‘British culture translation’ guide might make you smile. It has an application broader than EU translation of course, and works both ways too.

Check your power privilege. What might seem flippant, harmless or even funny between peers who know each other well, may come across as threatening to people who we are leading, managing, or supervising. This can be exacerbated if they are new to the task or workplace, are feeling a bit overwhelmed with workload, are on a steep learning curve, or are otherwise a feeling insecure about the work or career prospects they are getting feedback about.

Know what workplace bullying looks like. Keep an eye on yourself and others around you. Although I know I don’t need to preach to readers of this post about not using bullying as a feedback technique, there are those who feel they can get away with writing off their bullying behaviour as ‘just normal critical appraisal’, and may have normalised bullying at work, as part of the academic life. Rude and undermining behaviour isn’t just unpleasant in itself, it reduces motivation, engagement with and ownership of work, physical and mental health (see this study on workplace rudeness), and ultimately leads to isolation, low productivity, and delay.

Be specific about what you want to see. Have a wee laugh at this comedic example of poor feedback. And if you find you’re giving feedback like this, why not just do it better? Define what ‘good’ looks like through your feedback, for example on the elements and style of scholarly writing.

Use higher logical forms of disagreement. If you want to disagree, no problem. Just keep it about the subject of the disagreement, and keep away from the base of this hierarchy. Don’t troll your colleagues.

Try using ‘AND’ instead of ‘BUT’. You can easily negate good will by adding a ‘but’ after a positive statement. Try using ‘and’ instead. “You’re doing a great job here, and if you tried out one or two of these ideas, you could really become a connoisseur of feedback”. Remember that saying ‘however’ is just a fancy way of saying ‘but’. And saying, ‘on the other hand’ is just a metaphorical way of saying ‘but’. This is my personal top tip for feedback that lands well.

Try using ‘WHAT’ instead of ‘WHY’. Asking ‘why’ can (a) provoke defensiveness and make people feel the need to justify themselves, for example “Why didn’t you speak up about it?” [cue shame and regret] and (b) asking ‘why’ can send people spiralling backwards into the history of similar times they were stuck or frustrated and encourage self-blame. To keep ears open and minds solution-focused, try instead: “What would have made you more likely to express your views?” Because if we can define the ‘what’, we can create the ‘what’, and increase momentum.

Not shirk the difficult conversation. Sometimes we all have to speak an honest truth about someone’s habits, style or behaviour at work, and the impact it has on us. Things don’t get better on their own. Whatever difficult thing you have to say to your colleague(s), planning your conversation will help you clarify and articulate your thoughts and your approach, do give this type of conversation the time and thoughtfulness it deserves. Download a difficult conversation planning tool I made for the UK’s Future Leaders Fellows here.

If these ideas are useful, then please use them, adapt them and share them as you wish. If they aren’t useful, no worries. Remember that you don’t have to do all of the above, choose the right things for you. And if you do try out some of these ideas, your feedback is always welcome.