By Maleeha Rizwan, Researcher Development Specialist for Research Staff

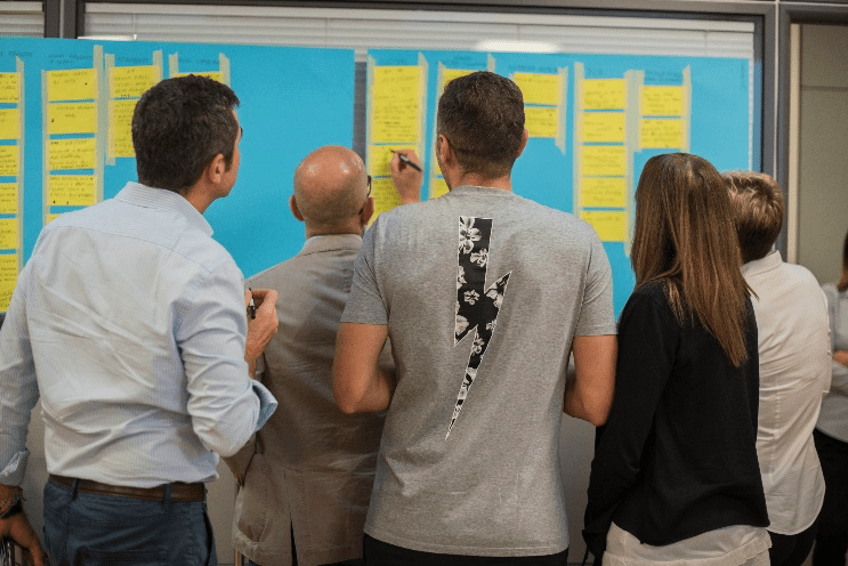

When people hear the word ‘facilitation’, they may often picture flipcharts, colourful slides, post-it notes and someone who comes in to ‘run’ the session, from the front. This can turn facilitation into a time-bound activity, limiting its perceived reach. The reality is that facilitation in any space, including within research, does not just happen in a workshop. It happens in supervision meetings, lab discussions, staff circles and brainstorming groups. A supervisor creating space for a feedback conversation, a PhD student helping a group navigate disagreement or a colleague pausing a discussion to check in if everyone has contributed. These moments are rarely formal or planned, yet they are practices that help to create a culture in which researchers thrive. These examples also show that responsibility for facilitation can be shared, regardless of where we sit in the room. Simply put, you are probably facilitating already.

Why facilitation matters in research culture

Research today is rarely a one-person job. Teams are large and complex, they cross disciplines and boundaries, collaboration is common and even for sole researchers, there is a need to negotiate with colleagues to acquire and share resources, and to actively participate in the discipline. At the same time, when pace, workload and demands are increasing (Elsevier, 2025), how we work together matters as much as the outputs we produce.

Wading through complex and overstretched systems is not easy; meetings can feel rushed, voices are unheard and positions can matter over process. Psychological safety underpins the workings of a positive research culture; and can make or break a space. Edmondson’s (2006) work on psychological safety has shown that people contribute best when they feel safe enough to belong, contribute and challenge. These conditions are often enabled by facilitative practices rather than formal or unspoken rules. Facilitation is embedded in everyday interactions; in redirection of energies and power, pauses to allow thinking, and use of curiosity over critique, which can foster trust, invite innovative ideas and surface assumptions that build the needed collective momentum.

Within diverse teams in the research community, where roles, knowledge and expertise are what we come armed with, facilitative practices in conversations can bring understanding and collegiality to the forefront. Teams across disciplines and functions bring rich ideas, but they also bring different ways of thinking and communicating. The power of facilitation in research cultures that are often siloed lies in reframing ‘difference’ as a strength, to empower people while being inclusive.

What facilitation can look like

How can one make facilitation an intentional practice? Often, the need for it becomes clear when a single question, pause or unexpected idea shifts a discussion. We have all had those moments, haven’t we? They are often small, but capable of reframing and reigniting a static discussion. Facilitation is not always easy, but its value lies in guidance rather than control. A tight grasp on the content of discussions, their structure and agendas, particularly in spaces that require curiosity and difference, can sometimes be counterproductive.

Below is a short list of facilitative practices that can form those needed small moments, inspired by Schwarz’s Ground Rules that show up in my practice as well.

- Focus on contribution over position: Rather than deferring to authority or hierarchy, welcome contributions from all. The levels of expertise or seniority in a room often shapes whose voices are heard first…or at all. Inviting perspectives from the room and checking in with quieter voices can shift the balance.

- Assume positive intent for shared understanding: Differing views can be daunting in spaces and may cause some voices to retreat before they have even spoken – I know I have experience this myself. Approaching difference and disagreements with curiosity, active listening and asking open/exploratory questions can help navigate tension constructively.

- Guide the process, not the content: One of the most challenging aspects of facilitation for me is letting go of the control we often feel we need. This may mean loosening tight agendas and adapting structure in response to group energy and dynamics. Light nudges and redirection can keep a conversation productive without stifling spontaneity.

- Observe and respond, not react: Facilitation relies on the group, not just the person in the front. This can include balancing the voices in the room, reframing conflict as difference and acknowledging that everyone shares responsibility for inclusion.

From this, what becomes clear is that facilitation could be anyone’s job because essentially, it’s about making space for everyone and sharing accountability for the process as well as the outcome. No titles, no hierarchy and plenty of curiosity. However, facilitation may not always be the right approach. Moments of urgency, risk or clear accountability may require decisive leadership rather than shared process.

How I have experienced facilitation

After working for years within talent, learning and researcher development now, I have only recently identified myself as a facilitator rather than a trainer or a teacher. In my previous role as the delivery lead of the Wellcome-funded Cynnau | Ignite research culture programme at Cardiff University, calling myself a facilitator in a room of researchers felt grounding – particularly as someone who is not a researcher. I came to see facilitation as a leadership skill I uniquely brought to that space and one that helped build trust with a community more accustomed to discussing expertise than experience. I did not have to own or be an expert in the content, rather guide my audience to make sense of it in their own ways.

At UofG, this has become even clearer through my involvement in College Concordat Working Groups and similar spaces. Facilitation becomes essential when balancing priorities, voices in the room and guiding community-led discussions. The Researcher Development Concordat offers a vast space for Researcher Developers to broaden their facilitative practice. The work connects various stakeholders in the research community to socialise the messages of the Concordat with researchers around their career and professional development – that’s facilitation!

As a recent venture, the recent InFrame Project on Embedding Collaborative Leadership for Leaders and facilitators in University of Edinburgh, University of Glasgow and University of St Andrews set out to upskill interested researchers and research professionals with practical tools and peer community that build confidence in facilitation as something we can all do. Development spaces, such as this project, for facilitators or for people to identify as one are vital to ensure continued empowerment, visibility and growth.

To conclude, if research culture is shaped by the everyday ways we meet, talk and decide, then facilitation does not belong to one person. When facilitative practices are embedded in labs, classrooms, meetings and workshops, we are better equipped to work with the complexities of research inclusively, collegially and curiously. That is the silent power of facilitation and why it belongs to all of us.