By Dr Qian Jiang, former PGR Intern and doctoral researcher in Education

The PGR Lived Experience Project, June – October 2025, was designed to listen to, value and better understand the lived experiences of two key groups of PGRs at the University of Glasgow: Part-Time PGRs, and PGRs who use English as an Additional Language (EAL-PGRs). Realised as a collaboration between Research Culture and Researcher Development and Research Governance, Policy and Integrity, the project was conceived as a staff-PGR collaboration, and centred a peer-led approach: PGR Interns took a leadership role in shaping the project strategically, designing the project methodology, and in gathering and analysing the data.

Qian led on the EAL-PGR branch of the project. In this blog she reflects on the project, and what she learned through being involved in this research.

Why I wanted to get involved in this project

As a researcher working towards completing a PhD using English as an Additional Language (EAL), I observed that many challenges that EAL-PGRs face were insufficiently articulated across the institution. I applied to join the project with a strong belief in the power of Research Culture and Researcher Development to drive positive change and promote a more inclusive research environment. I was excited to contribute my own research experience to this collaborative project.

Listening to the voices of EAL-PGRs

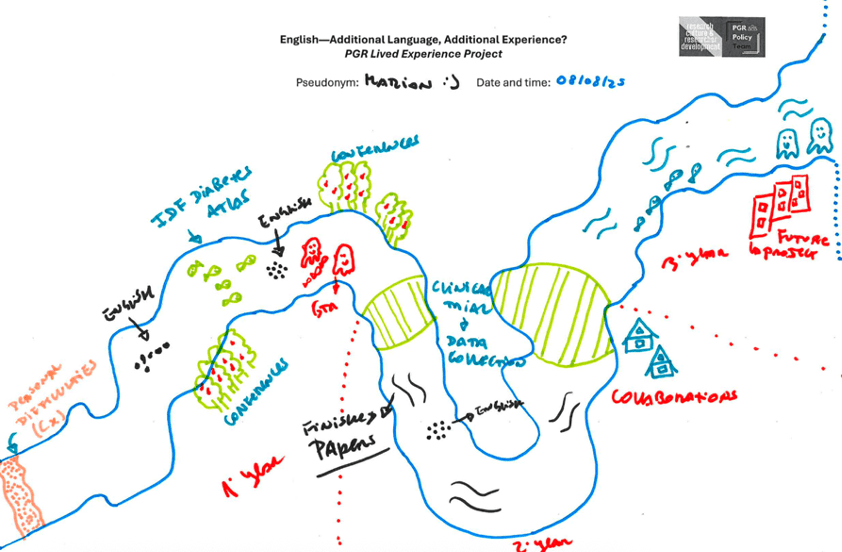

To create space for the voices of EAL-PGRs’ to be heard and valued, we designed six focus group sessions using a creative and inviting approach – the River of Experience (Elliot et al., 2024). This approach encourages participants to reflect on their experiences in a relaxing and imaginative way. In our project, it also created a space for participants to express themselves without the constrains of language, through drawing.

This was particularly important for this project. The 26 PGRs who participated in our focus groups spoke a combined total of 24 languages, indicating the rich linguistic diversity of the wider EAL-PGR community at University of Glasgow and diverse epistemologies and ways of communicating ideas that our participants hold. We were keen to have the opportunity to hear and value all of them through the focus groups.

EAL-PGRs reflected on their experiences, imagining their journeys as rivers flowing from the beginning of their studies to where they are now. 26 Rivers of Experience were generated, each unique, informative, and powerful in helping us connect with their journeys. In the second half of each focus group session, participants discussed several key themes including language use, inclusion, community building, and institutional support.

What did we learn?

Listening to the voices and the lived experiences of our EAL-PGRs, we learned:

![Image shows 6 drawings displayed side by side. The 6 drawings show details from 6 Rivers of Experience drawn by project participants during focus groups. Each image shows a different visual image which participants used to describe aspects of their PGR journeys. These are: 1. “seminars, talks, workshops, writing retreats” are “tributaries feeding into my river” ; 2. I am an “upside-down duck” in the river, because “I have troubles [in] expressing myself as I want to in English."; 3. “I basically slipped into this ravine”: “experimental failure and no accommodation"; 4. The “waterfall”: a perceived failure in the annual review"; 5. “The forest of unknown”: uncertain future"; 6. “difficulties to interact with people in the office – I am the only new one, only foreigner in the office.”](https://theauditorium.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/image-4.png?w=802)

2. I am an “upside-down duck” in the river, because “I have troubles [in] expressing myself as I want to in English.“

3. “I basically slipped into this ravine”: “experimental failure and no accommodation”

4. The “waterfall”: a perceived failure in the annual review

5. “The forest of unknown”: uncertain future

6. “difficulties to interact with people in the office – I am the only new one, only foreigner in the office.”

- EAL-PGRs deeply value dedicated writing support that is specifically tailored to their needs. They credited it with helping them understand both themselves and the UK context for academic practice better, and saving them time, among other things.

- Struggles in communicating in English are often invisible and internalised by EAL-PGRs, and experienced as a personal failure rather than an effect of wider structural or systemic issues. Many EAL-PGRs struggle with negative self-image, self-doubt and feelings of shame, blame and failure as a result.

- Many EAL-PGRs felt anxious or unsure about how they use AI technologies to support their language development and research practice. One researcher described AI as a “forbidden apple”, concluding “how can you not just take a bite?”.

- Language has an important but underexplored role to play in community building. For some EAL-PGRs, language brought them together, for others, it created barriers to connection, belonging and feeling valued.

- Several EAL-PGRs spoke of a transformational self-awareness experienced during their research journey: a growing understanding of their multilinguallity and associated epistemological and communicative richness. Realising that it took talent, skill and determination to undertake advanced research in an additional language reminded them of their abilities, and the value of their voices to the wider research culture.

What can institutions do to help?

The picture that emerges from the data, of which we have been able to share just a small part here, is rich and exciting and will be hugely valuable in enabling us to centre the experiences of EAL-PGRs as we design provision, plan policy enhancements, and work to lessen the impact of global structural inequities (Shahjahan 2025) and linguistic injustices (Melghan 2022) on the EAL-PGR experience at UofG.

Though our fuller recommendations, and a deeper analysis of the data can be found in our full report (to be published in early 2026), here’s our findings highlight what institutions could do to deepen their support for researchers who use EAL:

- Make it specific – Dedicated and tailored writing support has a powerful impact on skill development, self-understanding, self-belief, self-compassion, and personal growth. We recommend extending EAL-specific academic writing offers to include decolonially-informed speaking and listening support (Gimenez 2020).

- Make it visible – Increase visibility of challenges by offering specific materials, training and support to those who support EAL-PGRs.

- Make it smoother – EAL-PGRs described powerful moments of self-realisation that helped them value themselves more fully as English speaking academic researchers. Institutions can facilitate spaces where this transformational self-understanding can be realised, such as writing retreats, trainings, community events, or mentoring relationships.

- Make it integrated – Understand the connection between language and community building, explore linguistic diversity as an important space of connection around the discourses of belonging, feeling valued and mattering.

- Make it clear — Participants indicated that they would benefit from increased support around understanding the ethical use of AI. Universities could enhance practice in this area through training in policy translation, ethical prompt formulation, citational practice, and alternative writing and editing strategies.

My personal reflections

I think that the language barrier for EAL-PGRs is tangible and multidimensional. This is not because people are unwilling to make the effort, or careless about the clarity of their communication. Rather, they are likely doing their best, but the time required to fully engage with an additional language might not yet be available to them. I have even encountered tacit blame directed at EAL-PGRS, as if their language skills are a disruption, not an asset. This is something no researcher should have to experience. Together with the findings of this project, it suggests that in some academic spaces, a negative or false perception of linguistic diversity persists, affecting EAL-PGRs experiences. Looking ahead, this project is one, perhaps the first critical step forward in raising awareness complex issues around working in EAL, and the role of tailored, evidence-informed support in shaping equitable doctoral experiences.

*This blog is written with great acknowledgements to the support provided by Dr Rachel Lyon. Heartfelt thanks also go to Dr Mikaila Jayaweera Bandara and Arianna Magyaricsova.

This work was funded by a Student Experience Strategy Team UofG Together fund.