By Dr Rachel Chin, Researcher Development Project Officer (University of Glasgow’s Talent Lab)

This is a multi-function blog post. On the one hand it is an announcement. On the other hand, it is an exercise in self-reflection. Many of you will have met me through Flourish, the career development programme for Research Staff that I currently lead. I am really pleased to share that I hope to meet many more of you through my new post as Researcher Development Specialist (Writing and Communications), which I will take up on the 1st August.

Announcements over, let me move on to my main aim. Specifically, I would like to use this post to share with you and reflect on three of my own learnings as an academic writer. None of these thoughts are groundbreaking or even particularly insightful. And yet, in moments of writing frustration they frequently fall through the cracks.

Writing, academic or otherwise, is really difficult

Academic writing is about communicating quite complex ideas to a reader in an orderly fashion. Good academic writing will communicate these ideas clearly. It will make complicated arguments seem simple and straightforward, almost self-evident. It will organise the topic at hand and the unfolding of the argument and the evidence underpinning it in a logical and well-considered manner. In short, a good piece of academic writing will feel almost effortless in the way that it reads. I believe ‘elegant’ is the word that we often use to describe this calibre of writing.

This is difficult to achieve. I say this not to dishearten you, but rather to remind you (and myself for that matter) that academic writing takes time… a lot of time. Words, ideas and arguments do not always flow onto the page in the way that we would have hoped. Translating the muddle of facts and findings in our heads can be less straightforward than we think it ought to be.

Sometimes the way in which we think of ourselves as academics places most of the emphasis on research – the act of doing research whether in a lab, through fieldwork or in an archive. In this formulation writing can get shunted to one side. The act of writing up research is not as important as the research itself. However, taking the lead of scholars such as Pat Thomson, Rowena Murray, Sarah Moore and WriteSpace founder Helen Sword I would argue that these processes are of equal value. Without the written record no research can be communicated, shared, tested or debated.

Moreover, the process of writing up research is never simply an exercise in conveying straightforward facts. Academic writing, no matter what discipline, is about interpreting and giving meaning to research findings. These arguments and analyses are underpinned by research evidence, but they are conveyed through your voice, and it is your writing that gives you the power to persuade.

Don’t wait for inspiration to strike

The act of writing is often romanticised. Most of us are probably familiar with Jamie from the film ‘Love Actually’ sitting down to write in an idyllic lakefront cottage, pecking away at a vintage typewriter. If you have not seen Love Actually, you are nevertheless probably familiar with the idea of waiting to sit down to write until it feels ‘right’. The problem is, and I speak from experience here, inspiration does not always arrive when expected. Or, when it does peer out from whatever rock it has hidden under, you might be two glasses of wine in and what seemed brilliant in the moment appears as nonsensical paragraph-long sentences the following day.

The hard truth is that sometimes it is necessary to sit down and start writing even when you do not feel like it. Just as lab, library or archive-based research takes discipline and commitment, writing too deserves this same courtesy. The formulation, reformulation and refinement of ideas and findings through writing is an inherent and critical part of our process as researchers. In other words, writing is not just the transfer of research findings onto paper. It is the process of giving meaning and significance to those findings.

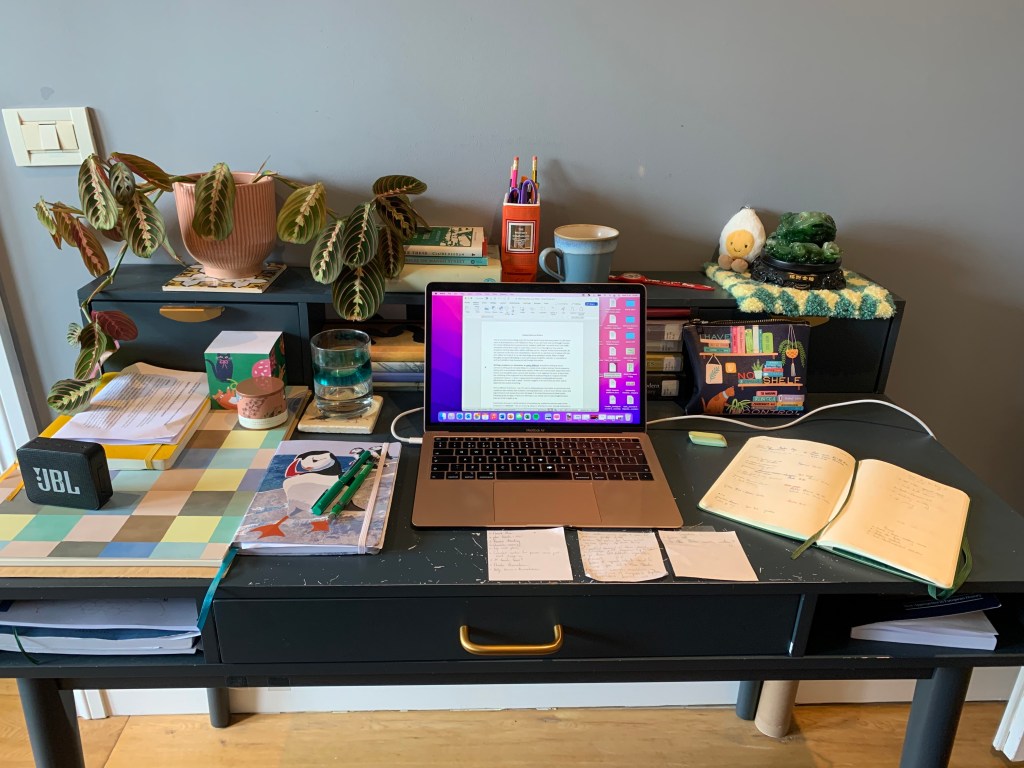

That being said, even if you are not waiting for inspiration to strike (and really, who wants to wait around to be struck by anything) there are things you can do to encourage the flow of ideas. Think about what kind of environments you write best in and try to recreate these spaces. For me, this can vary from day to day, but generally I write best in the morning in a quiet space. Sometimes I like to write in a café, where the gentle buzz of conversation can motivate and invigorate me. Generally, I do not like writing with others because the pull to chat is too distracting.

Take some time to think about what works for you or what feels right for you on the day. Are other people in the room a motivation or a distraction? Do you want music on? If so, do you want it aloud or in headphones? Does having a hot drink to hand facilitate pauses for reflection?

There’s no such thing as one size fits all

One of the most egregious concepts in contemporary consumption is the idea that one size can possibly fit everyone. Even so, it is not uncommon to find socks, capes and even dresses marketed in this way. The same can be said for academic writing. The writing that you produce and the process by which you get there is unique to you.

The individuality of academic writing does not mean that you are isolated. Nor does it mean that your approach to academic writing is set in stone. The beauty of writing is also in sharing, of writing itself, but also of writing practices and approaches. You will discover new techniques and approaches by speaking to friends and colleagues, by attending writing workshops and retreats, by reading widely and simply by reflecting on what works for you.

Being able to access a range of writing techniques does not mean that you need to deploy them all. Take what speaks to you and set the rest aside. And, if your usual approach to academic writing does not feel as effective as usual do not be afraid to change things up. Writing practices are not static. They can vary depending on what you are writing or how you are feeling on a given day. I go through long stretches where I write at a desk in my bedroom. But I also go through long stretches where I cannot bear my desk and I write at my dining room table.

The point of all of this is to say that writing, academic or otherwise, deserves our utmost consideration. I think often of something that a mentor told me a few years ago: that the most difficult thing to do in writing is to make complex ideas seem simple. This idea suffuses all my writing. More importantly, I think that it honours the time, care and attention that academic writing, as a process and a product, should receive.

In my new role I look forward to supporting the development of individual, collaborative and community writing practices. It will be my particular aim, at the start of this post, to speak to a wide range of individuals and groups engaged in the practice and support of academic writing and to understand how I can best support these diverse communities. I am excited about the knowledge that I will gain through this role as I have the chance to co-create writing support that speaks to and across the University of Glasgow’s research ecosystem.

Well written post, with points that I can really relate to, no merely as an academic writer, but as a (former) regular blogger. My best blog posts were always the ones that I had taken time and care to craft and refine – likewise, my favourite first-author paper. Thanks for these reminders, Rachel. 🙂

LikeLike