By Dr Udeni Salmon, EDI Consultant and researcher

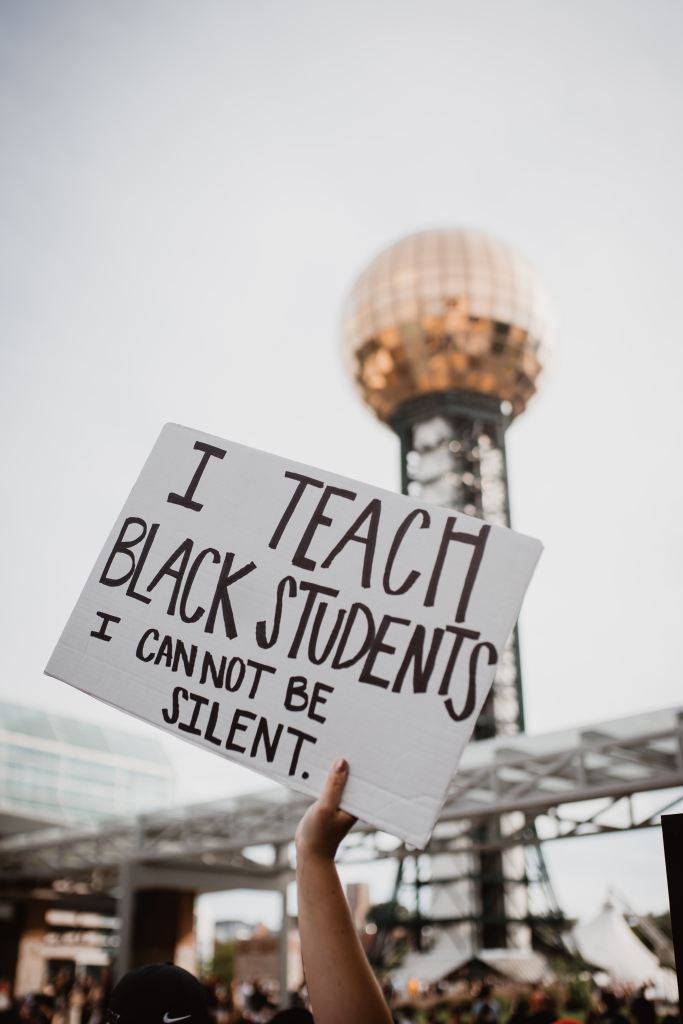

In Summer 2023, the Research Culture and Researcher Development team at the University of Glasgow invited me to develop an Anti-Racist Supervisor workshop for their doctoral supervisors. I was delighted by this invitation, as it suggested that the team are aware of the fact that White-dominated pedagogies too often fail students of colour, and that anti-racism in the HE classroom is an urgent and necessary response.

Black students and academics continue to be under-represented in high-quality research in the United Kingdom. In 2019, 11% (or 2285 of the 21,055) professors in the UK were BAME, with gender imbalances also present, and more pronounced among professors than other academics. In 2018, there were 25 Black female professors in the UK. What’s more, 0% of the COVID-19 research funding available in the first round of funding (2020) was given to Black researchers.

My previous research has suggested that EDI strategy within the academic research environment fails to support intersectional characteristics, with Black women at particular risk of hypervisibility, microaggressions and failure to be promoted. In the course of my research, I found only 84 peer-reviewed papers on gendered racism in research environments in higher education that were published globally between 1977 and 2019, a tiny fraction of the body of literature available on Higher Education research.

The diminishing presence of Black researchers in senior positions show us that traditional pedagogies fail students of colour for a number of structural and individual reasons.

Why do traditional pedagogies fail students of colour?

My research conducted at the University of Lincoln in 2019 involved interviewing women of colour who were scientists, PhD students, and also their supervisors and lab leaders. My findings are summarised below:

- Academic excellence is defined by what can be achieved by white, straight, able-bodied, cis-gender men: individuals who have similar research interests to their peers, who are able to participate in ‘pub culture’, and whose research output is uninterrupted by caring responsibilities. Depictions of a scientist or academic are generally that of a white man: often similar to Albert Einstein with his tweed jacket. Minoritized postgraduate researchers are more likely to have had unconventional career trajectories and, even when they have not, discrimination has hindered their ability to publish and to find funding.

- HR policies, particularly in academic research roles and doctoral supervision, are not consistently enforced: good practice around preventing and responding to bullying and harassment, racial, gender, sexuality and disability discrimination, sick leave and performance review should be fairly and consistently put into practice by HR and academic line management. Minoritized postgraduate researchers and Research Staff reported that the enforcement of existing HR policies was considered as important as developing new policies that were specifically aimed at race and gender discrimination.

- Microaggressions are commonly experienced: unintended or intended – participants reported frequent examples of insults and exclusions. In my research, an example given was of a Lab Technician who assumed that a black postgraduate researcher would be watching a royal wedding, because she identified with Meghan Markle. The PGR was taken aback but wanted to believe that the technician had good intentions. Subsequently, the technician asked her whether she would be interested in research about black slugs…because she was black. At this point, she decided that his intentions were part of a campaign to belittle and humiliate her.

- Researchers like to believe they are objective and that science operates outside politics and complex, messy human society. Researchers can therefore be reluctant to admit that their workplaces are racist and gendered, or that they themselves can hold these attitudes. Academics are, in general, liberal and therefore find it hard to acknowledge they benefit from Whiteness or maleness. White feminists can be a particular barrier for women of colour.

An effective anti-racist pedagogy should be founded on the knowledge of racism, as well as a good knowledge of your students. While specific strategies may vary depending on the context, there are several key elements that contribute to an effective anti-racist doctoral pedagogy. Some of these elements include:

Firm and consistent boundaries

Culture change, as Aiko Bethea has suggested, requires unacceptable behaviours to be firmly and consistently addressed. Postgraduate researchers in labs have complained of racism and sexism from a range of team members. Supervisors should not accept excuses and gaslighting from within their teams, such as “It was not my intention to offend anyone”, or “You are blowing this out of proportion”.

We urge doctoral supervisors to consider how they would address conflict in their teams, how to set and maintain boundaries so as to reduce negative interactions and prevent future conflict. Where supervisors spot problems that they cannot solve alone, we encourage them to feel confident in taking up issues with more senior colleagues and stakeholders.

Doing the reading

If a supervisor does not research in the fields of anti-racism, gender, disability or other marginalised characteristics, they should frequently update themselves on the latest thinking. Academics such as Guilaine Kinouani write regularly in the Race Reflections blog on their experiences of postgraduate education. Sara Ahmed’s Feminist Killjoys blog examines issues of Whiteness, racism and the limits of EDI within higher education.

Role-modelling a commitment to diversity

Doctoral supervisors are role models for their PGRs and must demonstrate a genuine commitment to EDI by setting clear goals, allocating resources, and holding themselves accountable for progress. Equally, supervisors should communicate with their researchers on how they will support their team to enforce boundaries and how they will take responsibility for difficult conversations with senior leaders.

Guidance from internal and external expertise

Staff and PGR EDI groups are an important resource for supervisors, who could ask to attend meetings, either alone or with their researchers, to access internal support for themselves and their teams, to understand the latest thinking on EDI within the University and to collaborate on ideas and solutions.

Help your PGR develop their ‘Science Identity’

‘Science identity’ is a concept developed by Carlone and Johnson (2007), whereby Black women scientists develop a race- and gender-inflected definition of themselves as scientists (or academics). This concept is relevant to all minoritised postgraduate researchers, regardless of discipline. Supervisors can help their researchers build a science identity by supporting them to extend their scientific community to include other minority scientists, to bring scientific knowledge to their families and communities through outreach and impact programmes, and by providing visible ways in which researchers can demonstrate their competence.

Supervisors exert a powerful influence in shaping the next generation of academics. By putting in the effort to understand anti-racism and role modelling inclusion in their teaching, supervisors can transform their PGRs’ experiences of higher education. As we strive for a just and equitable world, supervisors can, in bell hooks’ words ensure that “the classroom remains the most radical space of possibility”.